1 Overview

This assignment created 3D imagery using ray tracing instead of rasterization. In most other respects, its logistics are similar to the previous assignment.

1.1 Ray Emission

Rays will be generated from a point to pass through a grid in the scene. This corresponds to flat projection,

the same kind that HW2’s frustum matrix achieved. Given an image w pixels wide and h pixels high, pixel (x, y)’s ray will be based the following scalars:

s_x = {{2 x - w} \over {\max(w, h)}}

s_y = {{h - 2 y} \over {\max(w, h)}}

s_x and s_y correspond to where on the screen the pixel is: s_x is negative on the left, positive on the right; s_y is negative on the bottom, positive on the top. To turn these into rays we need some additional vectors:

eye- initially (0, 0, 0). A point, and thus not normalized.

forward- initially (0, 0, -1). A vector, but not normalized: longer

forwardvectors make for a narrow field of view. right- initially (1, 0, 0). A normalized vector.

up- initially (0, 1, 0). A normalized vector.

The ray for a given (s_x, s_y) has origin eye and direction forward + s_x right + s_y up.

1.2 Ray Collision

Each ray will might collide with many objects. Each collision can be characterized as o + t \vec{d} for the ray’s origin point o and direction vector \vec{d} and a numeric distance t. Use the closest collision in front of the eye (that is, the collision with the smallest positive t).

1.3 Illumination

Basic illumination uses Lambert’s law: Sum (object color) times (light color) times (normal dot direction to light) over all lights to find the color of the pixel.

Make all objects two-sided. That is, if the normal points away from the eye, invert it before doing lighting.

Illumination will be in linear space, not sRGB like the previous several assignments. You’ll need to convert RGB (but not alpha) to sRGB yourself prior to saving the image, using the official sRGB gamma function: L_{\text{sRGB}} = \begin{cases} 12.92 L_{\text{linear}} &\text{if }L_{\text{linear}} \le 0.0031308 \\ 1.055{L_{\text{linear}}}^{1/2.4}-0.055 &\text{if }L_{\text{linear}} > 0.0031308 \end{cases}

2 Required Features

The required part is worth 50%

- png width height filename

- same syntax and semantics as previous assignments.

- sphere x y z r

Add the sphere with center (x, y, z) and radius r to the list of objects to be rendered. The sphere should use the current color as its color (also the current shininess, tecture, etc. if you add those optional parts).

Add the sphere with center (x, y, z) and radius r to the list of objects to be rendered. The sphere should use the current color as its color (also the current shininess, tecture, etc. if you add those optional parts).For the required part you only need to be able to draw the outside surface of spheres.

- sun x y z

Add a sun light infinitely far away in the (x, y, z) direction. That is the

Add a sun light infinitely far away in the (x, y, z) direction. That is the direction to light

vector in the lighting equation is (x, y, z) no matter where the object is.Use the current color as the color of the sunlight.

For the required part you only need to be able to handle one light source.

- color r g b

Defines the current color to be r g b, specified as floating-point values; (0, 0, 0) is black, (1, 1, 1) is white, (1, 0.5, 0) is orange, etc. You only need to track one color at a time. If no

Defines the current color to be r g b, specified as floating-point values; (0, 0, 0) is black, (1, 1, 1) is white, (1, 0.5, 0) is orange, etc. You only need to track one color at a time. If no colorhas been seen in the input file, use white.You’ll probably need to map colors to bytes to set the image. All colors ≤ 0.0 should map to 0, all colors ≥ 1 should map to 255; map other numbers linearly (the exact rounding used is not important).

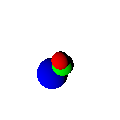

- Overlap

Your rays should hit the closest object even if there are several overlaping.

Your rays should hit the closest object even if there are several overlaping.

- sRGB

- Your computations should be in a linear color space, converted to sRGB before saving the image. This is reflected in the colors of every reference image on this page.

- Rays, not lines

Don’t find intersections behind the ray origin.

Don’t find intersections behind the ray origin.

3 Optional Features

3.1 Geometry (5–50%)

- Handle interiors (requires

bulb) (10%)  Correctly render when the camera is inside a sphere

Correctly render when the camera is inside a sphere

- plane A B C D (5%)

defines the plane that satisfies the equation Ax + By + Cz + D = 0

defines the plane that satisfies the equation Ax + By + Cz + D = 0

- Triangle (requires plane) (15%)

Add

Add xyzandtrifcommands, with the same meaning as in HW2 (except ray-traced, not rasterized).- Interpolate triangles (requires triangle) (5–20%)

Triangles can have values interpolated in ray tracing using Barycentric coordinates. Examples of values to interpolate:

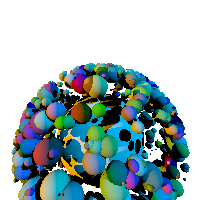

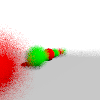

3.2 Acceleration (requires multiple suns and shadows) (30%)

Add a spatial bounding hierarchy so that hi-res scenes with thousands of shapes can be rendered in reasonable time.

The basic idea of a bounding hierarchy is simple: have a few large bounding objects, each with pointers to all of the smaller objects they overlap. Only if the ray intersects the bounding object do you need to check any of the objects inside it.

For good performance, you’ll probably need a hierarchy of objects in a tree-like structure. In general, a real object might be pointed to from several bounding objects.

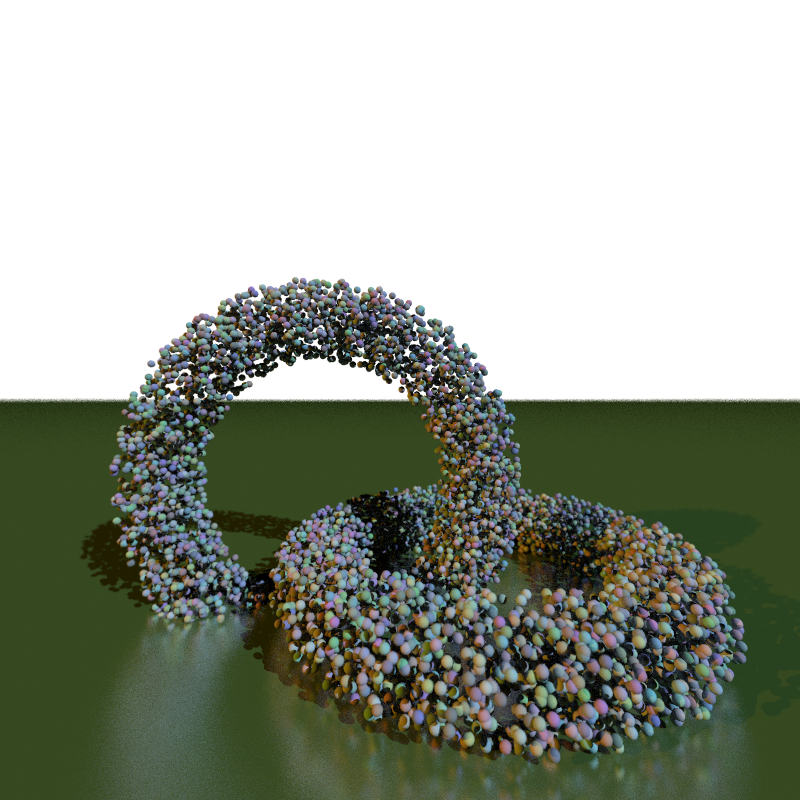

Rather than try to inspect your bounding hierarchy code, we’ll say you’ve achieved acceleration if you can render the scene shown here (which contains 1001 spheres, two suns, and shadows) in less than a second. And yes, this is arbitrary wall-clock time on our test server, and yes this does disadvantage people writing in Python (which is tens to hundreds of times slower than the other languages people are using in this class).

Rather than try to inspect your bounding hierarchy code, we’ll say you’ve achieved acceleration if you can render the scene shown here (which contains 1001 spheres, two suns, and shadows) in less than a second. And yes, this is arbitrary wall-clock time on our test server, and yes this does disadvantage people writing in Python (which is tens to hundreds of times slower than the other languages people are using in this class).

3.3 Lighting (5–70%)

- Multiple

suns (5%)  allow an unlimited number of

allow an unlimited number of suncommands; combine all of their contributions;- bulb x y z (requires multiple suns) (10%)

Add a point light source centered at (x, y, z). Use the current color as the color of the bulb. Handle as many

Add a point light source centered at (x, y, z). Use the current color as the color of the bulb. Handle as many bulbs andsuns as there are in the scene.Include fall-off to bulb light: the intensity of the light that is d units away from the illuminated point is 1 \over d^2.

- Negative light (requires

bulb) (5%)  Allow light colors to be less than zero, emitting

Allow light colors to be less than zero, emitting darkness

.- Shadows (10–30%)

No new commands for this one: you get these points if objects always cast shadows, you don’t if they don’t.

No new commands for this one: you get these points if objects always cast shadows, you don’t if they don’t.10 points for 1 sun, +5 if planes work, +5 if triangles work, +5 if multiple light sources work, +5 if bulbs work

- expose v (10%)

Render the scene with an exposure function, applied prior to gamma correction. Use a simple exponential exposure function: \ell_{\text{exposed}} = 1 - e^{\displaystyle -\ell_{\text{linear}} v}.Fancier exposure functions used in industry graphics, such as FiLMiC’s popular Log V2, are based on large look-up tables instead of simple math but are conceptually similar to this function.

Render the scene with an exposure function, applied prior to gamma correction. Use a simple exponential exposure function: \ell_{\text{exposed}} = 1 - e^{\displaystyle -\ell_{\text{linear}} v}.Fancier exposure functions used in industry graphics, such as FiLMiC’s popular Log V2, are based on large look-up tables instead of simple math but are conceptually similar to this function.- gi d (requires

aa, shadows, andtrif) (20%)  Render the scene with global illumination with depth d. When lighting any point, include as an additional light the illuminated color of a random ray shot from that point.

Render the scene with global illumination with depth d. When lighting any point, include as an additional light the illuminated color of a random ray shot from that point.These secondary

global illumination

rays should use all of your usual illumination logic to pick their color, including shininess, transparency, roughness, and so on if you’ve implemented them. However, a global illumination ray should only spawn another global illumination ray if d > 1, with the total number of global illumination rays generated capped by d.Distribute the random rays to reflect Lambert’s law. A simple way to do this is to have the ray direction be selected uniformly from inside a sphere centered at the tip of the normal vector with a radius equal to the normal vector’s length.

3.4 Materials (5–65%)

- shininess s (10%)

Future objects have a reflectivity of s, which will always be a number between 0 and 1.

Future objects have a reflectivity of s, which will always be a number between 0 and 1.If you implement transparency and shininess, shininess takes precident; that is,

shininess 0.6andtransparency 0.2combine to make an object 0.6 shiny, ((1-0.6) \times 0.2) = 0.08 transparent, and ((1-0.6) \times (1-0.2)) = 0.32 diffuse.Per page 153 of the glsl spec, the reflected ray’s direction is

\vec{I} - 2(\vec{N} \cdot \vec{I})\vec{N}

… where \vec{I} is the incident vector, \vec{N} the unit-length surface normal.

Bounce ech ray a maximum of 4 times unless you also implement

bounces.- shininess s_r s_g s_b (5%)

Future objects have a different reflectivity for each of the three color channels.

Future objects have a different reflectivity for each of the three color channels.

- transparency t (requires

shininess) (15%)  Future objects have a transparency of t, which will always be a number between 0 and 1.

Future objects have a transparency of t, which will always be a number between 0 and 1.Per page 153 of the glsl spec, the refracted ray’s direction is

k = 1.0 - \eta^2 \big(1.0 - (\vec{N} \cdot \vec{I})^2\big) \eta \vec{I} - \big(\eta (\vec{N} \cdot \vec{I}) + \sqrt{k}\big)\vec{N}

… where \vec{I} is the incident vector, \vec{N} the unit-length surface normal, and \eta is the index of refraction. If k is less than 0 then we have total internal reflection: use the reflection ray described in

shininessinstead.Use index of refraction 1.458 unless you also implement

ior. Bounce ech ray a maximum of 4 times unless you also implementbounces.- transparency t_r t_g t_b (5%)

Future objects have a different transparency for each of the three color channels.

Future objects have a different transparency for each of the three color channels.

- ior r (requires

transparency) (5%)  Set the index of refraction for future objects. If

Set the index of refraction for future objects. If iorhas not been seen (or if you do not implementior), use the index of refraction of pure glass, which is 1.458.- bounces d (requires

shininess) (5%)  When bouncing rays off of shiny and through transparent materials, stop generating new rays after the dth ray. If

When bouncing rays off of shiny and through transparent materials, stop generating new rays after the dth ray. If bounceshas not been seen (or if you do not implementbounces), use 4 bounces.- roughness \sigma (requires

shininess) (10%)  If an object’s roughness is greater than 0, randomly perturbed all three components of the surface normal by a gaussian distribution having standard deviation of \sigma (and then re-normalize) prior to performing illumination, refaction, or reflection.

If an object’s roughness is greater than 0, randomly perturbed all three components of the surface normal by a gaussian distribution having standard deviation of \sigma (and then re-normalize) prior to performing illumination, refaction, or reflection.

- Textures (10%)

This involves at least one command (for spheres) and possibly a second (for triangles, if used)

- texture

filename.png  load a texture map to be used for all future objects. If

load a texture map to be used for all future objects. If filename.pngdoes not exist, instead disable texture mapping for future objects.Assume the texture is stored in sRGB and convert it to a linear color space prior to using it in rendering.

The texture coordinate used for a sphere should use latitude-longitude style coordinates. In particular, map the point at

- the maximal y to the top row of the texture image,

- the minimal y to the bottom row,

- the maximual x to the center of the image,

- the minimal x to center of the left and right edges of the image (which wraps in x),

- the maximal z to the point centered top-to-bottom and 75% to the right, and

- the minimal z to the point centered top-to-bottom and 25% to the right.

The standard math library routine

atan2is likely to help in computing these coordinates.See also Interpolate triangles for the

texcoordandtritcommands.- texture

3.5 Sampling (5–65%)

- eye e_x e_y e_z (5%)

change the

change the eyelocation used in generating rays- forward f_x f_y f_z (10%)

change the

change the forwarddirection used in generating rays. Then change theupandrightvectors to be perpendicular to the newforward. Keepupas close to the originalupas possible.The usual way to make a movable vector \vec{m} perpendicular to a fixed vector \vec{f} is to find a vector perpendicualr to both (\vec{p} = \vec{f} \times \vec{m}) and then change the movable vector to be perpendicular to the fixed vector and this new vector (\vec{m}\prime = \vec{p} \times \vec{f}).

- up u_x u_y u_z (requires forward) (5%)

change the

change the updirection used in generating rays. Don’t use the providedupdirectly; instead use the closest possibleupthat is perpendicular to the existingforward. Then change therightvector to be perpendicular toforwardandup.- aa n (15%)

shoot n rays per pixel and average them to create the pixel color

shoot n rays per pixel and average them to create the pixel color

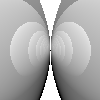

- fisheye (10%)

find the ray of each pixel differently; in particular,

find the ray of each pixel differently; in particular,- divide s_x and s_y by the length of

forward, and thereafter use a normalizedforwardvector for this computation. - let r^2 = {s_x}^2 + {s_y}^2

- if r > 1 then don’t shoot any rays

- otherwise, use s_x

right, s_yup, and \sqrt{1-r^2}forward.

- divide s_x and s_y by the length of

- panorama (10%)

find the ray of each pixel differently; in particular, treat the x and y coordinates as latitude and longitude, scaled so all latitudes and longitudes are represented. Keep

find the ray of each pixel differently; in particular, treat the x and y coordinates as latitude and longitude, scaled so all latitudes and longitudes are represented. Keep forwardin the center of the screen.- dof focus lens (requires aa) (10%)

simulate depth-of-field with the given focal depth and lens radius. Instead of the ray you would normally shoot from a given pixel, shoot a different ray that intersects with the standard ray at distance focus but has its origin moved randomly to a different location within lens of the standard ray origin. Keep the ray origin within the camera plane (that is, add multiples of the

simulate depth-of-field with the given focal depth and lens radius. Instead of the ray you would normally shoot from a given pixel, shoot a different ray that intersects with the standard ray at distance focus but has its origin moved randomly to a different location within lens of the standard ray origin. Keep the ray origin within the camera plane (that is, add multiples of the rightandupvectors but notforward.If you do

dofandfisheyeorpanorama, you do not need to (but may) implementdoffor those alternative projections.

3.6 Speed

For real raytracers, speed is all-important: the amount of fancy things an artist can afford to do is based on how quickly the basics can be handled. These scenes are not for credit, but will give you some examples to play with if you want to try to get your code fast.

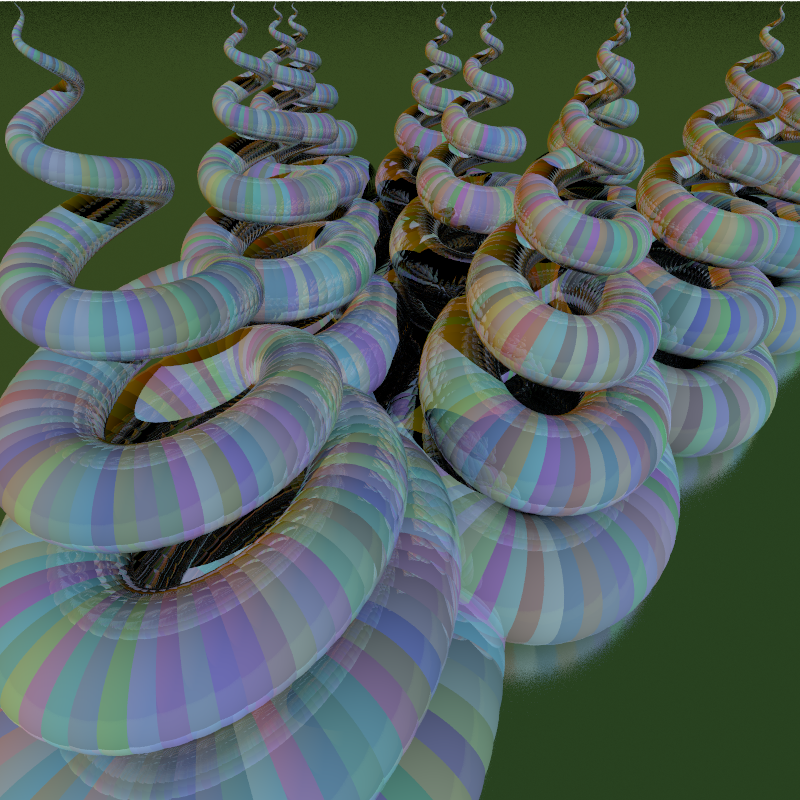

My reference implementation can render this image in just under 1 minute on my desktop computer or just under 4 minutes on my laptop. It makes use of multiple suns, shadows,

My reference implementation can render this image in just under 1 minute on my desktop computer or just under 4 minutes on my laptop. It makes use of multiple suns, shadows, aa, dof, shininess, roughness, and plane. If I disable all of those, it runs in 0.2 seconds (desktop) or 0.8 seconds (laptop). This scene also is suitable for an even faster implementation (maybe a 10× speedup) because its objects are all about the same size, have little overlap, and are roughly evenly distributed across the scene.

This image has half as many spheres and half the anti-aliasing of the previous image, but takes almost as long (50 seconds on my desktop) because the spheres vary a lot in size and overlap a lot, which makes acceleration more difficult.

This image has half as many spheres and half the anti-aliasing of the previous image, but takes almost as long (50 seconds on my desktop) because the spheres vary a lot in size and overlap a lot, which makes acceleration more difficult.

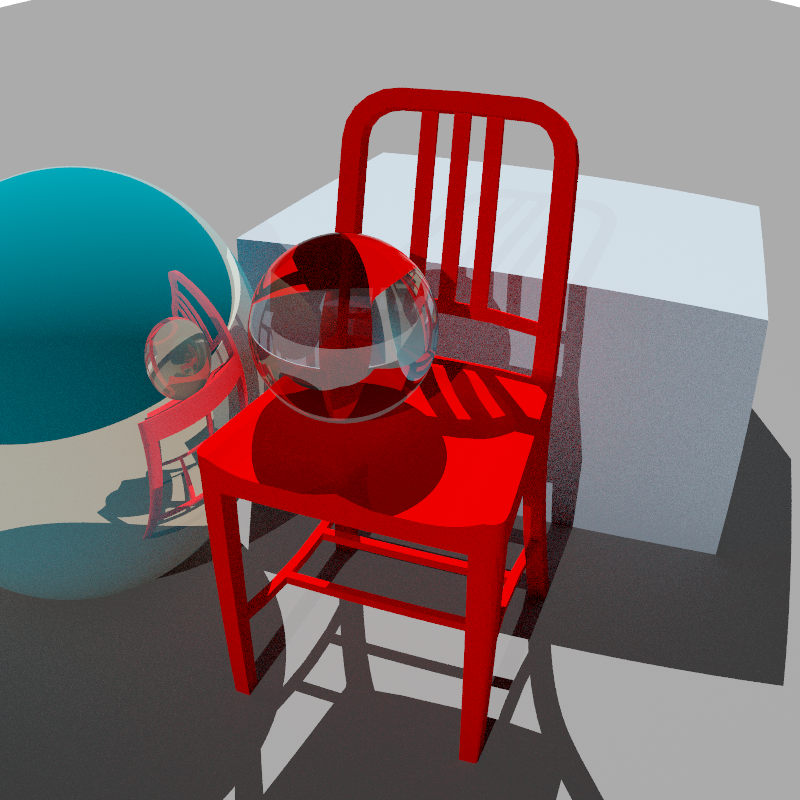

This image has 1715 triangles, 1 plane, and 2 spheres. It uses shadows, transparency, shininess, anti-aliasing, exposure, fisheye, and global illumination. On my desktop my reference implementation renders it in 55 seconds.

This image has 1715 triangles, 1 plane, and 2 spheres. It uses shadows, transparency, shininess, anti-aliasing, exposure, fisheye, and global illumination. On my desktop my reference implementation renders it in 55 seconds.